- Write a short analysis of mise-en-scene in Mandy (200-250 words), focusing on a memorable moment or scene. You can add this to the WordPress blog as a ‘Review’ (rather than a reading).

I really doubt that Godard would have called the scene I am going to describe as one of those “privileged moments” in films. However, this scene, in particular, stands out to me for its bizarreness concerning style and narrative. It happens shortly after Mandy was brutally burnt alive in front of her lover Red by a sadistic religious cult. Red is coming inside their home just after going through Mandy’s ashes. This next scene feels entirely in contrast with anything else.

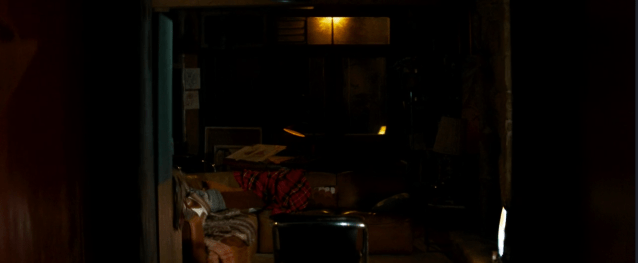

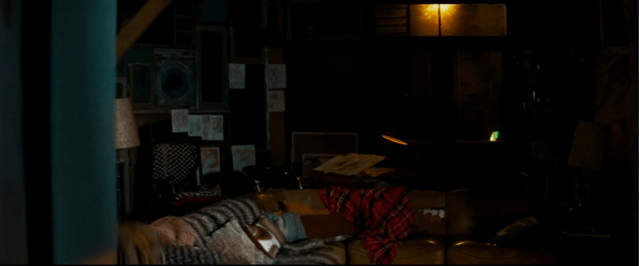

The camera moves from inside the house. We can see Mandy’s drawings on the wall and Red’s lumberjack shirt on the sofa. The room is dark save from the light from the television and the lightbulb outside.

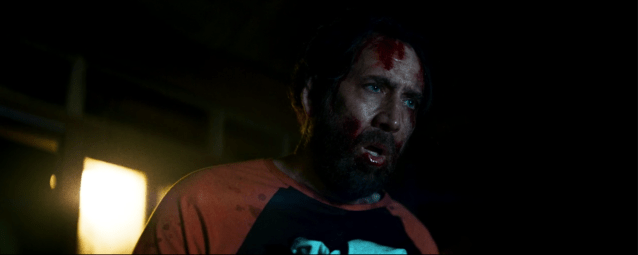

The camera stops at the entrance. We see Nicolas Cage character enter the room in a state of shock, covered in blood, wearing a kitsch sweater with a tiger on it and only his underwear. He finds on the floor Mandy’s jumper, and he picks it up.

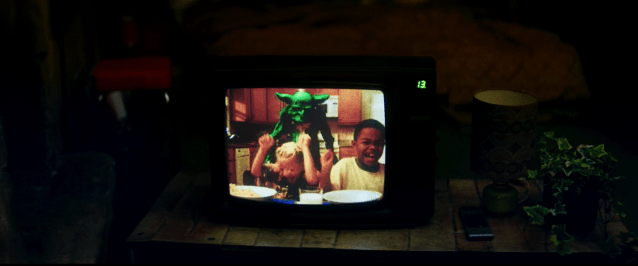

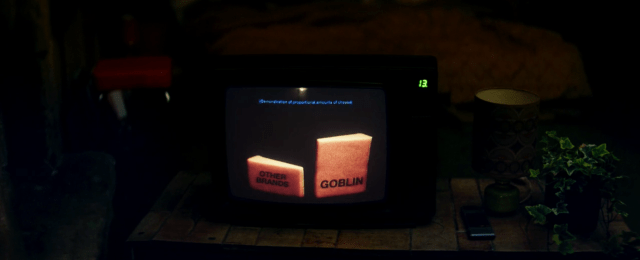

It cuts to the television screen, placed at the centre of the shot, where a grotesque and disturbing cheddar advert is playing. Reminiscent of 80’s horror aesthetic of B-Movies like the Troll 2, and the Gremils. We see a group of green goblins regurgitating cheese on two overly enthusiastic children.

Red is as hypnotised by the television screen, sharing the same bewilderment of the audience. At the end of the advert, we see a demonic goblin slowly emerging from the cheese. Something is deeply unsettling about the eyes of the goblin looking towards the audience, almost like if an insidious darkness entered Red and Mandy’s peaceful home and belongings.

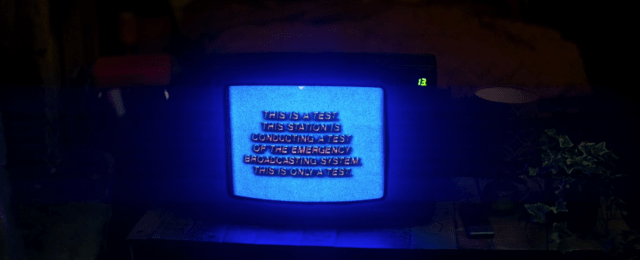

Red leaves the screen, going towards the bed, while we are still looking at the television screen. A plain blue emergency broadcast test interrupts the regular channel. The written words on the screen underline how “this is just a test”, implying that there aren’t any real emergency.

Red collapse into bed still in shock.

- The readings by Lavik and McWhirter cover similar issues, and will also recall ideas from Keathley’s piece on the video essay from Week 3. Thinking about all three pieces, identify 2 or 3 ‘key debates’ about audiovisual/video essays as a form of film criticism and/or film scholarship.

The Internet multimedia capabilities expanded immensely the possibilities for what constitutes film criticism. Now, we can access the vastness of information around film culture from the screen of our laptop. More comfortable, friendly-user editing softwares have made it possible for “amateurs” to learn editing skills. Moreover, digital criticism allows more flexibility and thanks to comment-sections, criticism is going towards what seems like an ongoing conversation about cinema rather than a verdict.

Finally, critics and scholars can incorporate moving images and sounds to their object of analysis. The opposite approaches that these new forms of criticism are shaping into, raise questions on the very definition of “video essay”.

In this multimedia spectrum, we have a more explanatory, analytical, language-based approach on the one hand, and a more poetic and expressive approach on the other. In “The Substance of Style” Matt Zollers Seitz closely analyses Wes Anderson’s entire body of work as well as his past influences and his substantial impact on contemporary filmmakers with a cohesive and precise 5 part video essay. Whereas Kevin B. Lee focuses on radical filmmaking, exploring the history of anti-colonialism by engagingly using little-known films. These video essays still rely a lot on the written language and spoken words, which according to Lavik it’s an essential part if you want to make a clear and articulate video essay which is not just ornamental.

On the other hand, the majority of these new audiovisual essays seems to borrow more elements from the avant-garde movements than from documentary practices. “Essay film” was a term coined in 1940 by experimental animator Hans Richter. They were abstract, difficult to grasp and at times impenetrable. Great filmmakers from the French Left Bank as Chris Marker and Alain Resnais were using visuals as their only language.

Jim Emerson’s “Close-Up” is a collage from classic films with no narration. The result is an evocative meditation on the medium of cinema itself. Others video essays seem more obsessed with smaller details, or patterns in films. For instance, Christian Marclay’s monumental collage “The Clock” is a looped 24-hour video montage of scenes from film and television that feature clocks.

Many of these audiovisual work better in art galleries than in academia presentation, more as a homage than a pondered evaluation.

Why is audiovisual criticism still at its embryonic state? Probably due to the technophobia of film critics and scholars who never learned to edit or lacked the resources. Often the most successful video essayists had a background in film practices. However, it seems like more and more critics are willing to learn these new skills or to collaborate with more technically skilful people. Now we have many digital platforms available dedicated exclusively or partially to video criticism, as Indiewire’s Press Play, Fandor’s Keyframe, and The Museum of the Moving Image.

The last issue concerns intellectual property. Many critics are unaware of their power when using copyright material. The Fair Use Act protects the audiovisual critic when it comes to using images and sound from films since the purpose is purely educational.

The piece on Mandy is well written and describes the sequence clearly, showing good attention to elements of mise-en-scene. The next step would be to analyse how these stylistic choices create meaning. For example, you could focus on analysing how emergency test signal creates a sense of irony (for Red, it is an emergency not just a test) but also links to the film’s systematic questioning of what is real (perhaps this IS just a ‘test’?).

There was one grammatical mistake: ‘there aren’t any real emergency’ mixes a plural verb (aren’t) with a singular noun (emergency); it needs to be ‘there isn’t any emergency’ instead. (I’d also change ‘sweater’ and ‘jumper’ to ‘long-sleeved t-shirt’; sweaters and jumpers are made of wool, whereas t-shirts are made of cotton. Helpfully, in English, ‘a jersey’ can mean sweater/jumper, but we’d also describe the kind of knitted fabric used for t-shirts as ‘cotton jersey’.)

LikeLike

The discussion of Lavik and McWhirter summarises a range of ideas from the readings. There’s a clear sense of your understanding although you could make the areas of debate more explicit, in order to answer the question more directly. This would also show the ability to extrapolate from the readings, by recognising the points they have in common. For example, you could have included a sentence at the beginning saying something like ‘three key areas of debate crop up in both readings: questions of form (from explanatory to poetic approaches); the need to develop technical skills; and the implications of copyright and intellectual property.

We should talk through how to reference sources of information more clearly. At the moment, most of this answer is written as if these are your own ideas and examples. You needed to make it clearer, for example, that Lavik discusses Matt Zoller Seitz and Jim Emerson, while McWhirter uses the example of Kevin B. Lee. Some of the phrasing is also too close to theirs, e.g. ‘ongoing conversation about cinema rather than a verdict’ are Lavik’s words exactly, and needed to be presented and referenced as a quotation. This is so that if you then drew on your blog for writing the essay (or another assignment), you would know where the words came from and could reference them correctly.

LikeLike