- How do the readings characterise/define ‘cult cinema’ and ‘trash cinema’?

Garfinkel stated that not all cult films are trash and not all trash films automatically receive a cult status. The two definitions often intermingle and their differences increasingly narrow. Cult Cinema incorporates a wide variety of films which are difficult to categorise. Popular films such as The Big Lebowski and Fight Club, film oddities such as Rocky Horror Picture Show and Harold and Maude and re-evaluated classics including Freaks and Peeping Tom are all considered cult movies.

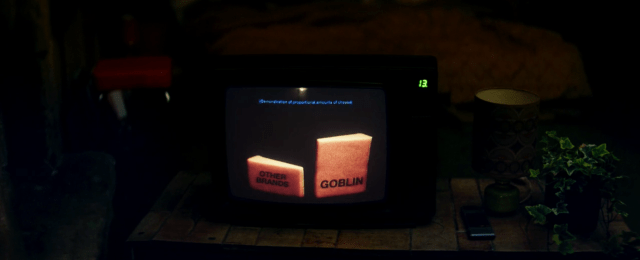

Trash Cinema is often linked to ‘exploitation films’, containing an abundance of violence, gore and nudity:

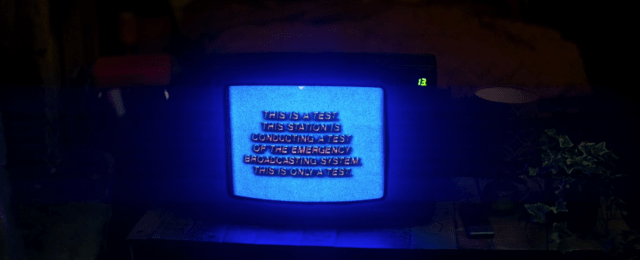

What defines cult is not the film itself, but its audience. It’s the fervent enthusiasm of its niche spectatorship that gives the cult status to non-mainstream films. The Midnight Movie became a cinematic phenomenon in the early ’70s when small theatres started late-night screenings of bizarre cinematic creations. Films like the acid western El Topo were screened at the Elgin Theatre in New York City, aiming at building an audience for counterculture films. In the 80’s the cult following moved to the small screen with the advent of videotapes. Usually, subgenres such as blaxploitation, sexploitation, Nazi exploitation, nunsploitation, Mondo films and Italian Giallo were released straight to VHS, also known as “video nasties”. The existence of distasteful horror was not ephemeral anymore. A moviegoer could own the film, pause it, rewatch it and rewind it several times.

Trash cinema is strictly related to class and sexuality. It became a form of expression for the marginalised voice in society, especially for queer audiences, critics and filmmakers. Andy Warhol, John Waters, Derek Jarman and Kenneth Anger treated “trash” as a crude form of artistic expression. It offered a shocking alternative to high culture and the mainstream to an audience bored by the formulaic “proper” model of Classic Hollywood Cinema.

All these films trasgressively refused conventional ideas of beauty and taste. They were vulgar, kitsch, camp, over the top and often surreal. Thus, they share many similarities with the surrealist movement (Dalí and Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou) as well as conceptual art (Duchamp’s urinal). “Trash cinema” is imbued with cultural fears and repressions and evokes the primordial scope of cinema to transform reality.

- What does cinephilia and cult cinema have in common?

Hunter analyses the subtle differences between cinephilia (which tends to be more interested in “high culture) and cult cinema (which tends to be more obsessed with “low culture”). However, the similarities are more than the contrasts. Mainstream Cinema seems to marginalise these modes of film watching. Whether you call them “film-maudits” or “film freaks”, they are films that are working outside the constrictions of Hollywood Studios and their rigid narrative formulas. Both audiences have a certain sensitivity and awareness towards what alternatives the film universe can offer. They both actively seek out rare gems, whether it is The Cabinet of Dr Caligari or Pink Flamingo. The line between the two gets thinner when Hitchcock’s Vertigo -which was labelled as trash when it came out- it’s now 1st on the BFI 100 Greatest Films of All Time. What was considered “trash” in the past might be considered “art” in the present and vice versa.

Both the cinephile and the cultist share the same appreciation for films authorship. They both celebrate the audacities of the creators and position the director on top of the hierarchy as an auteur. Filmmakers such as Argento, Fulci and Waters have distinctive trade-marks and idiosyncrasies which make them subjects of study and admiration.

- How do the authors conceptualise ideas around high and low culture? Do they mention the middle-brow?

“High Culture” is associated with ciné-clubs, European art-house screenings, film magazines, film festivals and Criterion Collection DVD editions. On the opposite side of the spectrum, “low culture” tends to be associated with American pop culture, Midnight movies, body horrors, Arrow films, naughty postcard, pulp novels and pornography. According to Hunter, the idea of “high art” was conceptualised with the advent of the modernist art movement which labelled as “junk” what was considered popular and accessible. “High art” is accessible only for those few with enough knowledge and interest to grasp it or appreciate it. “High culture” seems to be defined by critics and gate-keepers, whereas cult cinema is defined by its audience. Films considered to be part of “low culture” are often raw, poorly directed, and low budget. They aim for the spectators’ bodies rather than their minds. Low Culture is more often than not corporeal.

Hunter refers to the middle-brow in relation to films that once were acclaimed and then forgotten. The middle-brow seem to be the “forgettable”, textbook films made by American studios which are formulaic and generic and don’t stand the test of time.

Paul Schrader’s career is just astounding. Screen-writer for many of Scorsese’s masterpieces as Taxi Driver (1976), Raging Bull (1980), and The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), he is also a film critic, writer, and of course director of films like American Gigolo (1980) and Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985). His filmography is exceptionally varied and somewhat erratic. Giorgio Moroder and David Bowie’s modern soundtrack didn’t save his horror remake Cat People (1982) for me, and his Canyons (2013) starring Lindsay Lohan and porn actor James Deen was just unbearable.

Paul Schrader’s career is just astounding. Screen-writer for many of Scorsese’s masterpieces as Taxi Driver (1976), Raging Bull (1980), and The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), he is also a film critic, writer, and of course director of films like American Gigolo (1980) and Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985). His filmography is exceptionally varied and somewhat erratic. Giorgio Moroder and David Bowie’s modern soundtrack didn’t save his horror remake Cat People (1982) for me, and his Canyons (2013) starring Lindsay Lohan and porn actor James Deen was just unbearable.